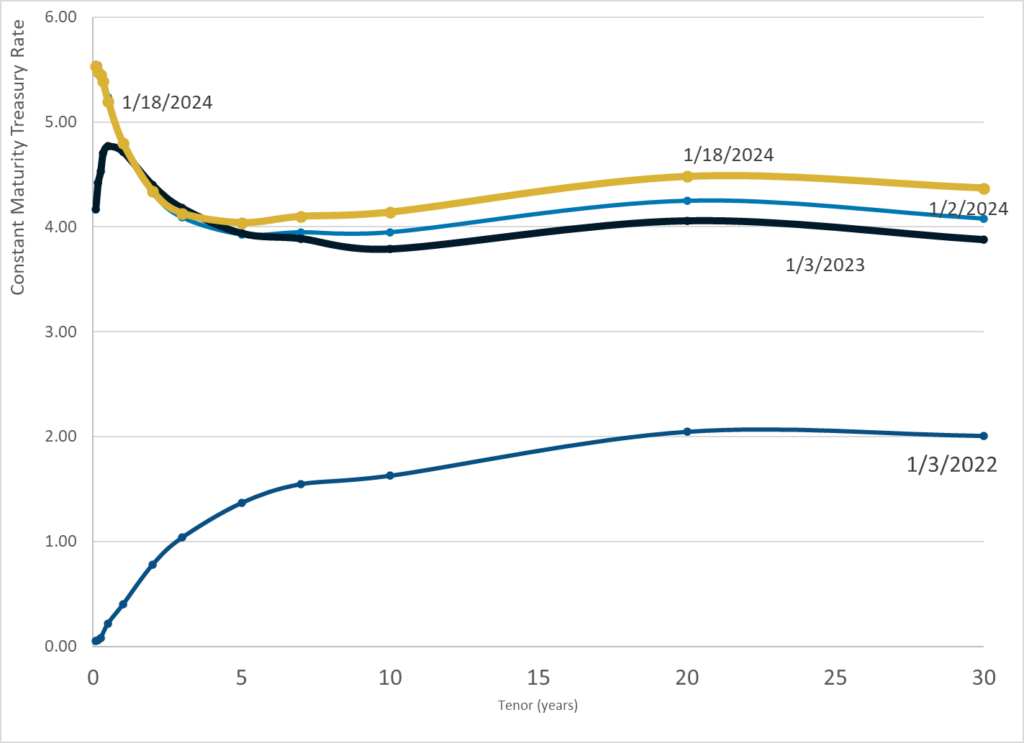

Graphic:

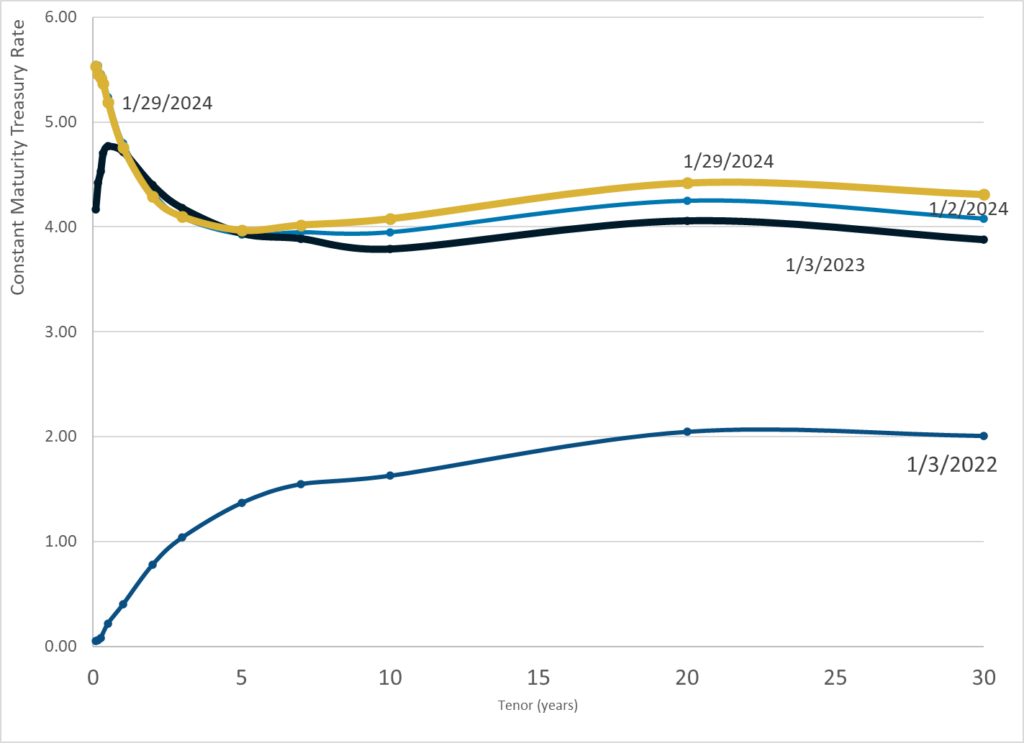

Publication Date: 29 Jan 2024

Publication Site: Treasury Dept

All about risk

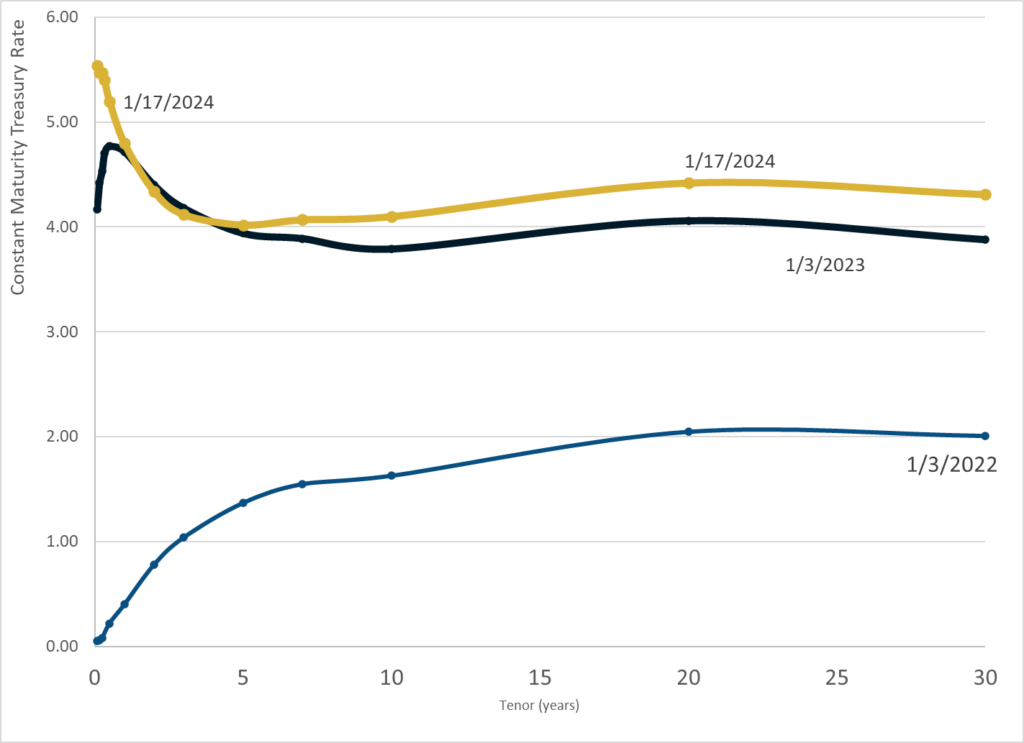

Graphic:

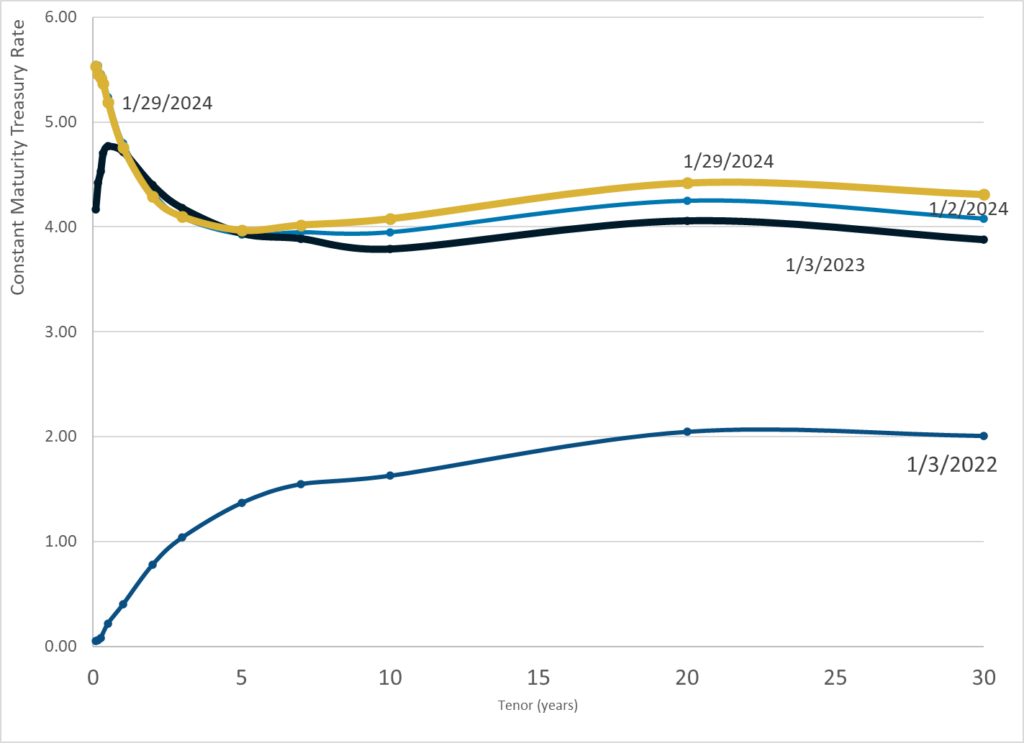

Publication Date: 29 Jan 2024

Publication Site: Treasury Dept

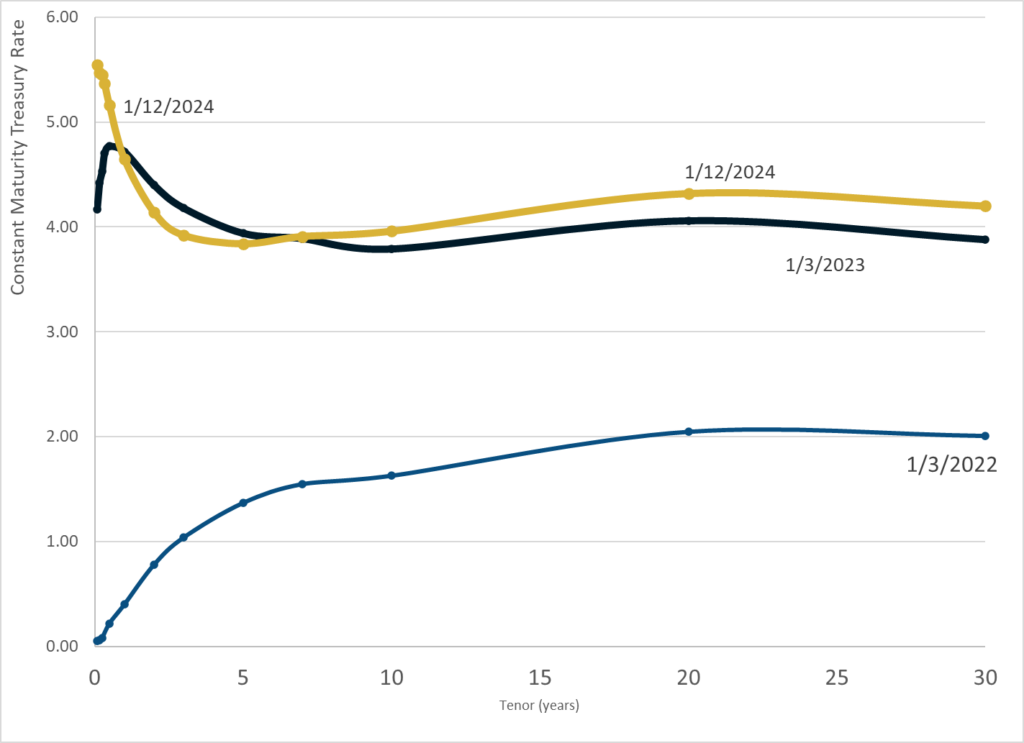

Graphic:

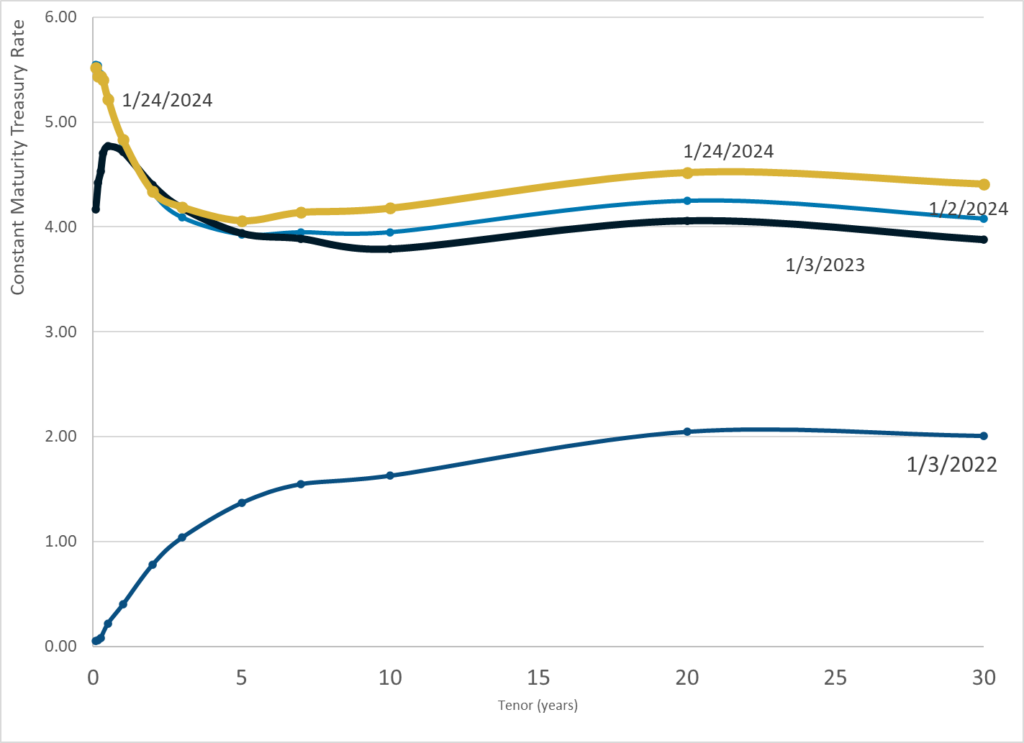

Publication Date: 24 Jan 2024

Publication Site: Treasury Dept

Link: https://www.cato.org/regulation/winter-2023-2024/will-actuaries-come-clean-public-pensions

Graphic:

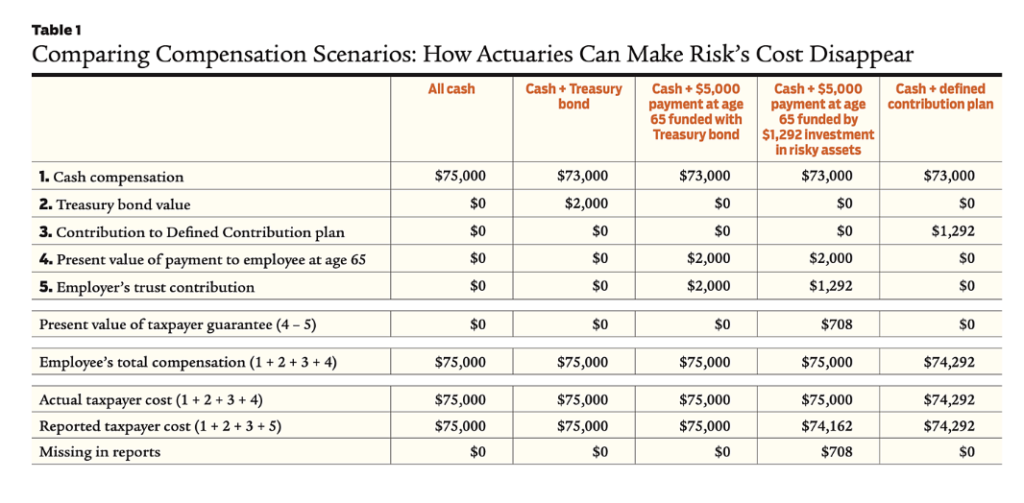

Excerpt:

To appreciate the significance of using inappropriate discounting, consider this example: A 45‐year‐old public sector employee earns $75,000 per year with no pension plan or other benefits. To help secure her retirement, her employer considers changing her compensation to $73,000 in salary plus a U.S. Treasury zero‐coupon bond that pays $5,000 in 20 years. The bond is selling in the market at $2,000. The Treasury bond’s implicit annual “discount rate” is thus 4.69 percent, i.e., $2,000 plus 4.69 percent interest compounded for 20 years equals $5,000.

The total compensation cost to the employer would remain $75,000. The employee, in turn, has three options:

Now suppose the public employer decides to be more paternalistic. Instead of giving the employee the Treasury bond worth $2,000, it promises her that in 20 years it will pay her $5,000. To fund this liability, the employer could deposit the $2,000 in a trust and have the trust buy the Treasury bond. The promise would then be fully funded by the trust. In 20 years, the Treasury bond would be redeemed for $5,000 and the proceeds forwarded to the employee. In the intervening 20 years, before the bond redemption and payment to the employee, the value of the future payment would increase with the passage of time, and increase (or decrease) as market interest rates decrease (or increase). But the value of the bond held in the trust would change identically to the liability, and the contractual obligation to pay $5,000 at age 65 would remain fully funded at every instant until paid, regardless of what happens in financial markets. Ignoring frictional costs and taxes, the employer’s cost of those actions would be the same as if it had paid the employee $75,000 in cash. And the employee’s total compensation would still be $75,000: $73,000 in cash plus a promise worth $2,000.

But instead of contributing the $2,000 and using it to buy the bond, the public employer could hire a public pension actuary and invest any trust contributions in a “prudent diversified” portfolio including assets, like equities, exposed to various market risks. The actuary would attest that the “expected” annual earnings of the portfolio over the long term is 7 percent (according to a sophisticated financial model). The actuary would then use the 7 percent to discount the $5,000 future payment and certify that the “cost” to the employer is $1,292, which is 35 percent less than the $2,000 cost of the Treasury bond. The actuary would certify that if the employer contributes the $1,292, its benefit obligation is “fully funded” because, if the trust earns the “expected return” of 7 percent (50 percent probable, after all), the $1,292 will accumulate to $5,000 in 20 years. The public employer can then claim it has saved taxpayers $708 ($2,000 – $1,292) by investing in a prudent diversified asset portfolio.

The question is, does it really cost only $1,292 to provide the same value as a $2,000 Treasury bond? Is $1,292 invested in the riskier portfolio worth the same as a Treasury bond that costs $2,000? Of course not. If it is possible to spin $1,292 of straw into $2,000 of gold, why would the government employer stop at pensions? Why not borrow as much as possible now and invest the proceeds in a prudent diversified portfolio expected to earn 7 percent and use the “expected” gains from taking market risk to pay for future general government expenditures?

The public employer is providing a benefit worth $2,000—a guarantee—and hoping to pay for it with $1,292 invested in a risky portfolio. The $708 difference represents the value of the guarantee that taxpayers will make good on any shortfall when the $5,000 comes due. The cost to taxpayers in total is still $2,000, but $708 is being taken from future generations by the current generation in the form of risk. Risk is a cost (precisely $708 in this example). Its price reflects the possibility as viewed by the market that future taxpayers ultimately may have to pay nothing at all if things go well, or a significant sum if they don’t.

Suppose the employer takes this logic one step further and, rather than promising $5,000 in 20 years, it contributes $1,292 to a defined contribution plan that invests in the same prudent diversified portfolio on the theory that the employee will be breaking even because the $1,292 is “expected” to accumulate to $5,000. The employee would be correct to view that as a cut in pay. The $708 cost of risk is shifted to the employee, reducing her compensation, instead of being borne by future taxpayers as in the case of the defined benefit plan.

The employee might complain. Future taxpayers cannot.

The only way for the employer to keep the employee whole with $73,000 of cash compensation plus a defined contribution plan is to contribute $2,000 to the plan. Whether it is invested in the Treasury bond or in riskier assets in the hope of higher returns, the value of her total compensation would still be $75,000.

Table 1 summarizes all these scenarios. The fourth column is the analog of public pension plans. Both the reported annual cost for the future $5,000 payment ($1,292) and the reported total compensation ($74,292) are understated. Investment professionals are paid well for managing risky assets for which high expected returns can be claimed. The actuary collects a fee. The employee has the value of the guarantee and bears none of the market risk being taken. Along with a happy employee, the public employer gets to report an understated compensation cost, freeing up money for other budget items. It’s good for all involved—except for the taxpayers on the hook for $708 in costs hidden by using the 7 percent discount rate.

Author(s): Larry Pollack

Publication Date: Winter 2023-2024

Publication Site: Cato Regulation

Report PDF: https://stand.earth/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/The-Hidden-Risk-in-State-Pensions-Report.pdf

Graphic:

Excerpt:

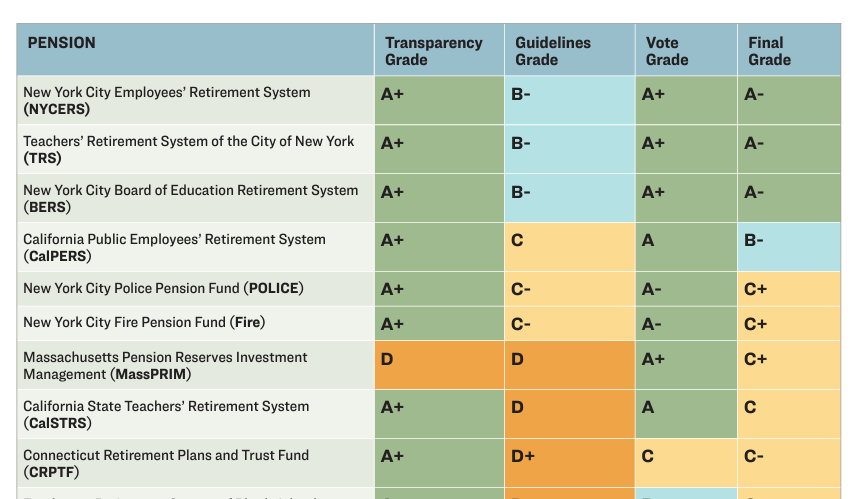

A first-of-its-kind report, the Hidden Risk analyzes the proxy voting records and proxy voting guidelines of the 19 public pensions that are in states where a state financial officer has indicated it is a priority issue both to advocate for more sustainable, just, and inclusive firms and markets , and to protect against climate risk.

Ahead of the 2024 shareholder season, a first-of-its-kind report “The Hidden Risk in State Pensions: Analyzing State Pensions’ Responses to the Climate Crisis in Proxy Voting,” from Stand.earth, Sierra Club and Stop the Money Pipeline, analyzes proxy voting records, proxy guidelines, and voting transparency of 24 public pension funds in the USA collectively representing over $2 trillion in assets under management (AUM).

These pensions are based in states where a state financial officer is a member of For the Long Term, a network that advocates for more sustainable, just, and inclusive firms and markets and strives to protect markets against climate risk.

The pensions analyzed include the pension systems of New York City and the states of California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Author(s):

Stand.earth

Sierra Club

Stop The Money Pipeline

Publication Date: 23 Jan 2024

Publication Site: Stand.earth

Graphic:

Publication Date: 23 Jan 2024

Publication Site: Treasury Dept

Graphic:

Excerpt:

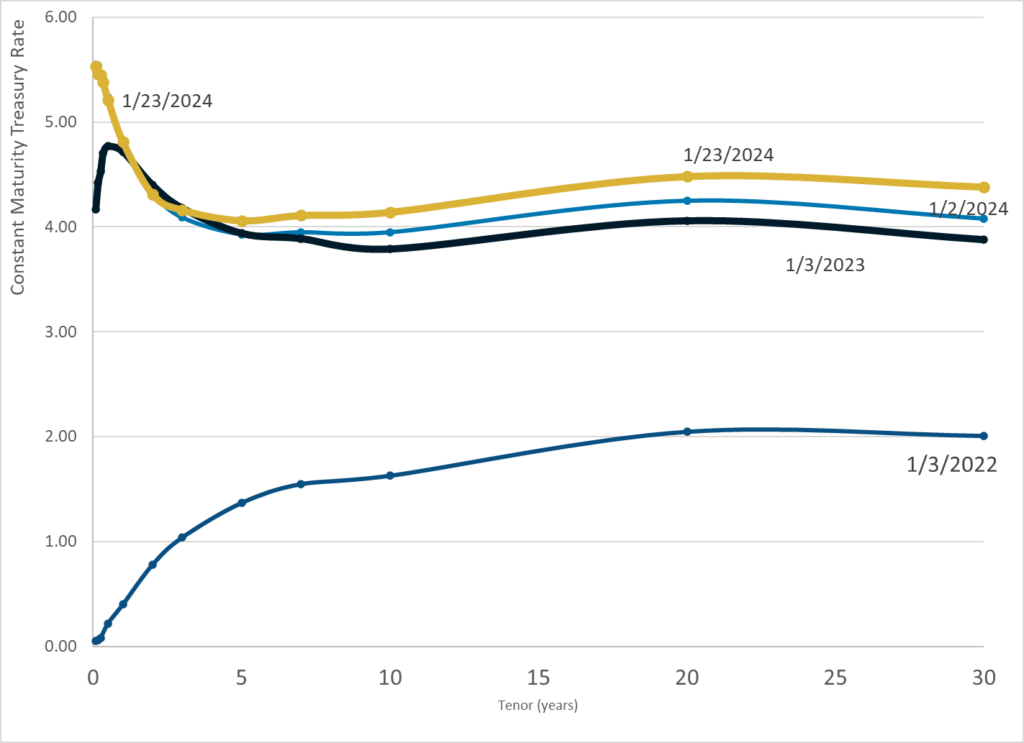

The purpose of this paper is to introduce the concept of capital and key related terms, as well as to compare and contrast four key regulatory capital regimes. Not only is each regime’s methodology explained with key terms defined and formulas provided, but illustrative applications of each approach are provided via an example with a baseline scenario. Comparison among these capital regimes is also provided using this same model with two alternative scenarios.

The four regulatory required capital approaches discussed in this paper are National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ (NAIC) Risk-Based Capital (RBC; the United States), Life Insurer Capital Adequacy Test (LICAT; Canada), Solvency II (European Union), and the Bermuda Insurance Solvency (BIS) Framework which describes the Bermuda Solvency Capital Requirement (BSCR). These terms may be used interchangeably. These standards apply to a large portion of the global life insurance market and were chosen to give the reader a better understanding of how required capital varies by jurisdiction, and the impact of the measurement method on life insurance company capital.

All of these approaches are similar in that they identify key risks for which capital should be held (e.g., asset default and market risks, insurance risks, etc.). However, they differ in significant ways too, including their defined risk taxonomy and risk diversification / aggregation methodologies, as well as required minimum capital thresholds and corresponding implications. Another key difference is that the US’s RBC methodology is largely factor-based, while the other methodologies are model-based approaches. For the model-based approaches, Solvency II and BIS allow for the use of internal models when certain conditions are satisfied. Another difference is that the RBC methodology is largely derived using book values, while the others use economic-based measurements.

As mentioned above, this paper provides a model that calculates the capital requirements for each jurisdiction. The model is used to compare regulatory solvency capital using identical portfolios for both assets and liabilities. For simplicity, we have assumed that all liabilities originated in the same jurisdiction as the calculation. As the objective of the model is to illustrate required capital calculation methodology differences, a number of modeling simplifications were employed and detailed later in the paper. The model considers two products – term insurance and payout annuities, approximately equally weighted in terms of reserves. The assets consist of two non-callable bonds of differing durations, mortgages, real estate, and equities. Two alternative scenarios have been considered, one where the company invests in riskier assets than assumed in the base case and one where the liability mix is more heavily weighted to annuities as compared to the base case.

Author(s): Ben Leiser, FSA, MAAA; Janine Bender, ASA, MAAA; Brian Kaul

Publication Date: July 2023

Publication Site: Society of Actuaries

Graphic:

Publication Date: 18 Jan 2024

Publication Site: Treasury Dept

Graphic:

Publication Date: 17 Jan 2024

Publication Site: Treasury Dept

Link:https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2024-01-17/making-esg-a-crime

Excerpt:

Oh sure whatever:

Republican lawmakers in New Hampshire are seeking to make using ESG criteria in state funds a crime in the latest attack on the beleaguered investing strategy.

Representatives led by Mike Belcher introduced a bill that would prohibit the state’s treasury, pension fund and executive branch from using investments that consider environmental, social and governance factors. “Knowingly” violating the law would be a felony punishable by not less than one year and no more than 20 years imprisonment, according to the proposal.

Pensions & Investments reports:

“Executive branch agencies that are permitted to invest funds shall review their investments and pursue any necessary steps to ensure that no funds or state-controlled investments are invested with firms that invest New Hampshire funds in accounts with any regard whatsoever based on environmental, social, and governance criteria,” the bill said.

The New Hampshire Retirement System “shall adhere to their fiduciary obligation and not invest with any firm that will invest state retirement system funds in investment funds that consider environmental, social, and governance criteria, as the investment goal should be to obtain the highest return on investment for New Hampshire’s taxpayers and retirees,” the bill said.

Investors aren’t allowed to consider governance! Imagine if this was the law; imagine if it was a felony for an investment manager to consider governance “with any regard whatsoever.”

….

I’m sorry, this is so stupid. “ESG” is essentially about considering certain risks to a company’s financial results: You might want to avoid investing in a company if its factories are going to be washed away by rising oceans, or if its main product is going to be regulated out of existence, or if its position on controversial social issues will cost it sales, or if its CEO controls the board and spends too much corporate money on wasteful personal projects. Obviously ESG in practice is also other, more controversial things:

But if you make it a crime for investors to consider certain financial risks then you get too much of those risks.

In particular, I suspect, you get too much governance risk. If every investor tomorrow said “okay we don’t care about the environment,” most companies probably wouldn’t ramp up their pollution: Their executives probably don’t want to pollute unnecessarily, polluting probably wouldn’t help the bottom line, and many companies just sit at computers developing software and couldn’t pollute much if they wanted to. But if every investor tomorrow said “okay we don’t care about governance,” then, I mean, “governance” is just a way of saying “somebody makes sure that the CEO is doing a good job and doesn’t pay herself too much.” If the investors don’t care about that, then a lot of CEOs will be happy to give themselves raises and spend more time on the corporate jet to their vacation homes.

Author(s): Matt Levine

Publication Date: 17 Jan 2024

Publication Site: Bloomberg

Excerpt:

In May, the United Kingdom’s version of the Securities and Exchange Commission will begin enforcing its pledge to crack down on so-called greenwashing by companies wishing to trade on the label of being green-friendly.

The Financial Conduct Authority’s rules, announced in late November, come as U.S. traders await stronger regulations from the SEC. That body moved in September to curb misleading marketing practices by requiring 80 percent of funds that claim to be “sustainable,” “green,” or “socially responsible” to actually be so.

The sustainability disclosure requirements are now deemed a necessity after regulators found “environmental, social, and corporate governance” analysts at Goldman Sachs and Germany’s DWS Group were promoting investments that were not as ESG-friendly as they claimed.

“The portfolio managers weren’t necessarily doing all of the work that they said they were doing,” the associate director of sustainability research for Morningstar Research Services LLC, Alyssa Stankiewicz, said. “They didn’t have documentation or data maybe related to the ESG-ness of these investments.”

At the same time as ESG-friendly firms are facing accusations of insincerity, they’re also coming under pressure from state pension funds in states with Republican-controlled governments that don’t want their employees’ retirement funds affected by what they view as politicized, left-leaning investing strategies.

Author(s): SHARON KEHNEMUI

Publication Date: 16 Jan 2024

Publication Site: NY Sun

Link: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-56718036

Excerpt:

The Post Office had prosecution powers and, between 1999 and 2015, it prosecuted 700 sub-postmasters and sub-postmistresses – an average of one a week – based on information from a computer accounting system called Horizon. Another 283 cases were brought by other bodies including the Crown Prosecution Service.

Some went to prison for false accounting and theft. Many were financially ruined, even though they had repeatedly highlighted problems with the software.

After 20 years, campaigners won a legal battle to have their cases reconsidered. To date only 93 convictions have been overturned. Under government plans, victims will be able to sign a form to say they are innocent, in order to have their convictions overturned and claim compensation.

….

Horizon was introduced by the Post Office in 1999. The system was developed by the Japanese company Fujitsu, for tasks like accounting and stocktaking.

Sub-postmasters complained about bugs in the system after it falsely reported shortfalls – often for many thousands of pounds.

Some attempted to plug the gap with their own money, as their contracts stated that they were responsible for any shortfalls. Many faced bankruptcy or lost their livelihoods as a result.

The Horizon system is still used by the Post Office, which describes the latest version as “robust”.

….

Nobody has ever been held accountable for the scandal.

The heavily criticised former Post Office chief executive, Paula Vennells, said she would hand back her CBE after a petition calling for its removal gathered more than a million signatures.

Lib Dem leader Sir Ed Davey is among several politicians who have faced questions, as he was postal affairs minister in the coalition government. He said he regretted not asking “tougher questions” of Post Office managers, describing what had happened as “dreadful”.

The inquiry is hearing from Post Office investigators, Fujitsu, civil servants and others.

Author(s): By Kevin Peachey, Michael Race & Vishala Sri-Pathma

Publication Date: 11 Jan 2024

Publication Site: BBC News

Graphic:

Publication Date: 12 Jan 2024

Publication Site: Treasury Dept